And yet, this region represents a picture-perfect Christmas postcard all on its own. Juliana Horatia Ewing knew this when, in 1867, she wrote the region's first Christmas story while living in Fredericton with her husband, Captain Alexander Ewing, an officer in Her Majesty's 22nd (Chesire) Regiment. The story, "The Three Christmas Trees", was published in the collection The Brownies and Other Tales (1886) and can be read online here. One hundred and fifty years later, Ewing's prose stills delights and the picture of that "small town of a distant colony" remains quaint, sure, but fits snugly into this spiritual narrative of the link between our world and the world beyond.

Flash forward to the 1950s where you will find these three hidden Nova Scotia gems: In The Wee Folk: About the Elves in Nova Scotia by Mary Alma Dillman (1953), the first story is "Xmas Eve in Teaberry Hollow" wherein Santa and Mrs Claus rescue Peter, the young elf who gets caught in a blizzard and becomes frozen solid; Alice Dagliesh rounds out her collection The Blue Teapot (1959) with the tale of a family who get their first set of electric Christmas lights; and Julia L. Sauer's 1951 novel, The Light at Tern Rock, tells of an eldery woman and a young boy who spend their Christmas tending a lighthouse off the coast of Nova Scotia.

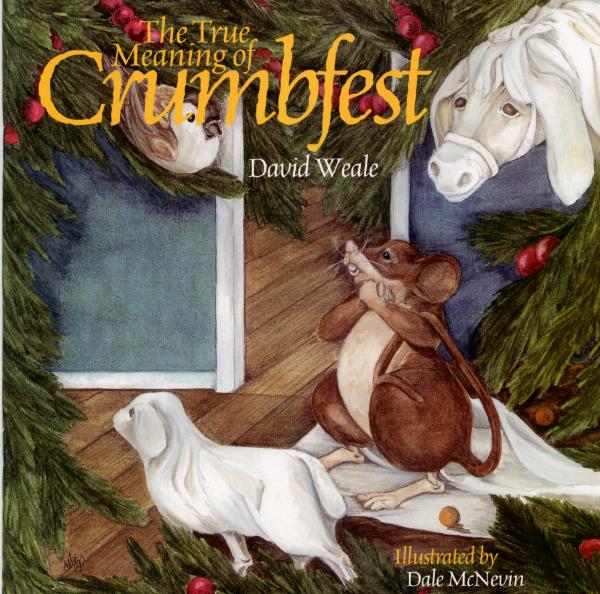

For an non-Avonlea take on Christmas in P.E.I. try David Weale's picture books, The True Meaning of Crumbfest (Acorn Press, 1999) and Everything that Shines (Acorn Press, 2001). In the former, a young mouse sets out to discover the origins of the plentiful crumbs that come to his people each year in late December. The latter is not so much a Christmas book, but rather a book about dealing with grief that happens to be set in the holiday season.

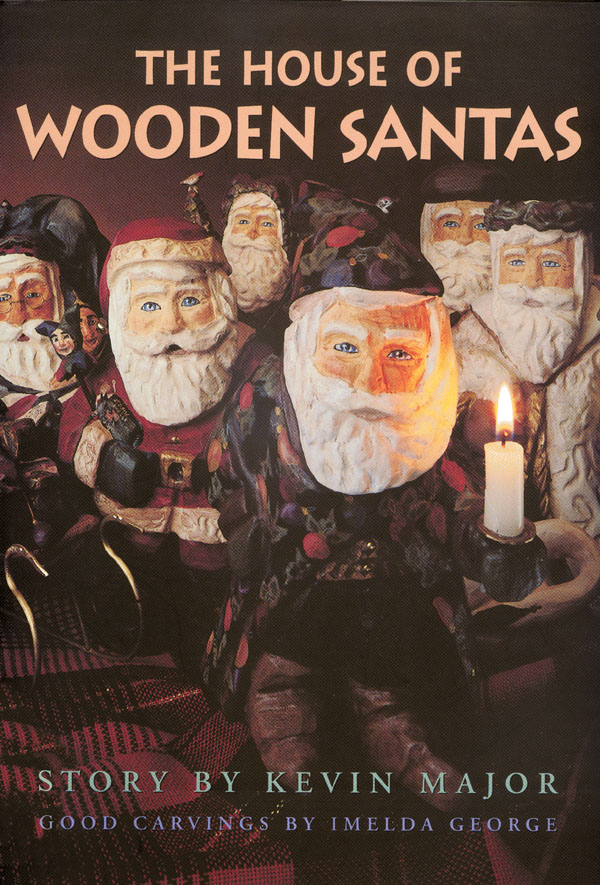

Newfoundland's Kevin Major has penned two contemporary Christmas classics: The House of the Wooden Santas (1997 Red Deer College Press) and Aunt Olga's Christmas Postcards (Groundwood, 2005).

The House of the Wooden Santas is an advent book with one vignette a day for the 24-day lead up to Christmas. As you can see from the illustration above, Imelda George's wood carvings add to the quirky yet lush feel of the book.

Aunt Olga's Christmas Postcards is a tribute to holiday picture postcards from all over the world. Images of hundred-year-old cards are combined with contemporary illustrations from Bruce Roberts as the tale (and poetry) of Aunt Olga and her family unfolds.

Finally, from Newfoundland is David Budge's The Mummer's Song, illustrated by Ian Wallace. This picture book is a simple rhyming tribute to the practice of mumming between Christmas and New Years' in rural Newfoundland. An afterword by Kevin Major explains the tradition to novices.

For additional Christmas books from the region, click over to the Portolan Bibliography where you can search "Christmas" and so much more besides.

This easy reader by the author of the Frog and Toad books is a masterpiece of literary minimalism. When the young narrator's parents get lost at sea, he is taken in by his aged Uncle. The book playfully explores youth vs age and naivety vs wisdom. It is a testament to grief and a quiet tribute to the love that can grow from mutual loss. The nonesensical elephant song that serves as the emotional climax of the book makes both me and my daughter very happy.

This easy reader by the author of the Frog and Toad books is a masterpiece of literary minimalism. When the young narrator's parents get lost at sea, he is taken in by his aged Uncle. The book playfully explores youth vs age and naivety vs wisdom. It is a testament to grief and a quiet tribute to the love that can grow from mutual loss. The nonesensical elephant song that serves as the emotional climax of the book makes both me and my daughter very happy.

Bob Staake's

Bob Staake's  from

from

From Rob Gonsalves'

From Rob Gonsalves'  Marie-Louise Gay's

Marie-Louise Gay's  Christopher Myers'

Christopher Myers'

From

From

In Janell Canon's

In Janell Canon's

Randolph Caldecott

Randolph Caldecott Kate Greenaway

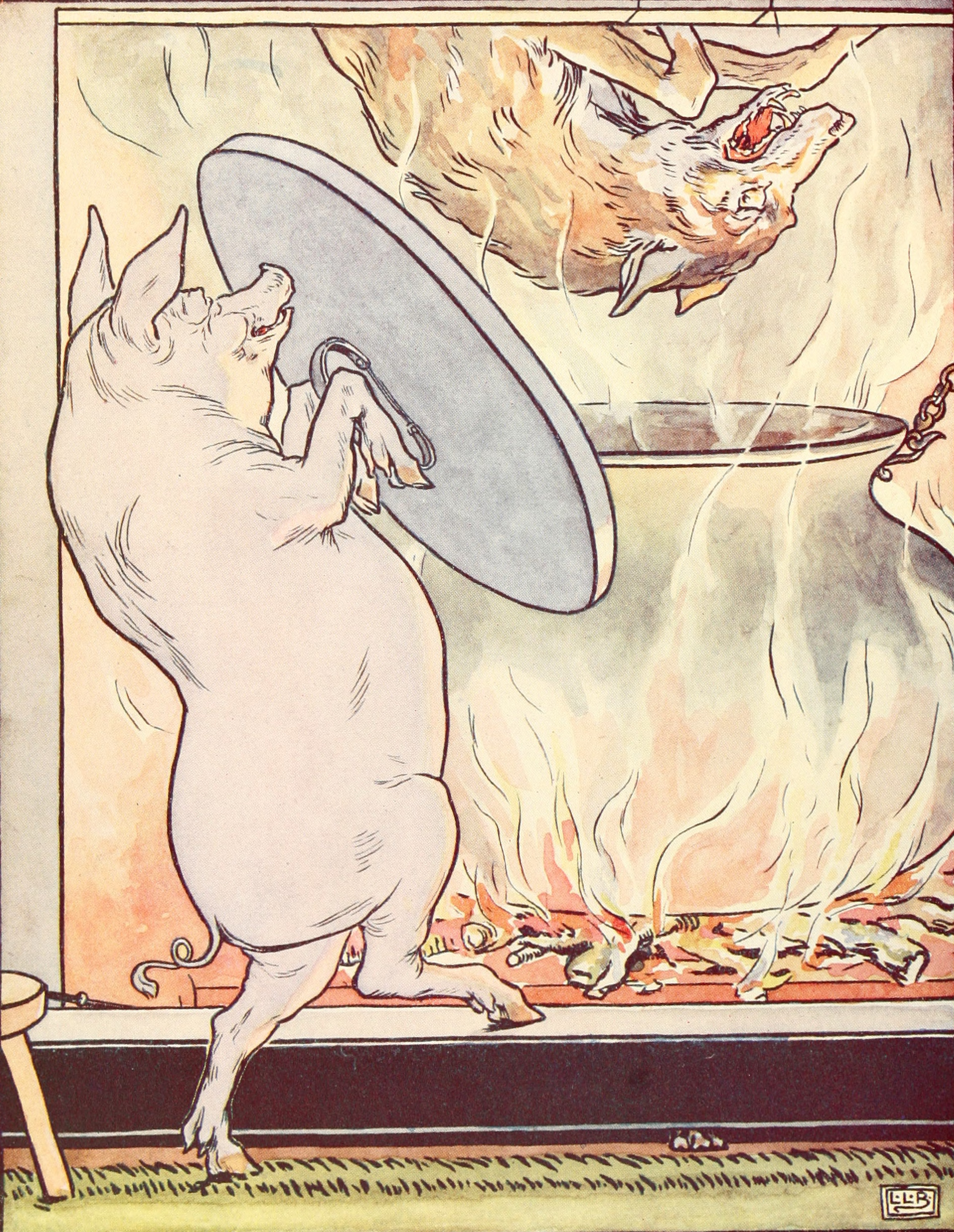

Kate Greenaway Leslie Brooke

Leslie Brooke

Vera B. Williams'

Vera B. Williams'

Leo and Diane Dillon's

Leo and Diane Dillon's  Ricardo Keens-Douglas'

Ricardo Keens-Douglas'  Gerald McDermott's

Gerald McDermott's